One of the things that I’ve been working on changing has been daily exercise. Since childhood, I have always enjoyed physical activity. From playing organized sports to individual activities such as walking, the physical and mental benefits of exercise have been rewarding. However, I also go through days (ok, weeks…) of inactivity. In fact, I would like to exercise more regularly, but something always seems to get in the way. Or does it? In other words, is it that my life is so busy that I cannot find time for physical activity, or am I making excuses for why I cannot exercise more often?

Thinking, Preparing, Acting, and Maintaining Change

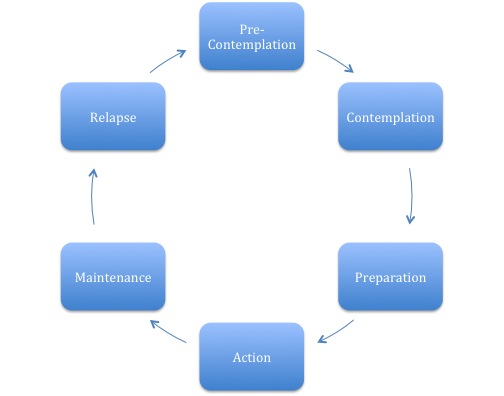

The first two stages in Prochaska’s and DiClemente’s Stages of Change model posits that before we decide to change any behaviour (e.g., to exercise more often), we first think about whether or not the new behaviour is worth adopting, and whether or not we even think there is a need for it. When we are often confronted with the need to change a behaviour, we may be resistant to change and even deny that there is a behavioural problem in the first place. This type of thinking is known as Precontemplation. When we are in the Precontemplation stage, we do not even recognize or acknowledge that something needs to change. For example, an alcoholic will deny they have a drinking problem despite being repeatedly told by loved ones that their drinking is damaging their relationships. “I don’t have a problem; YOU have a problem!” is an example of what someone in the pre-contemplative stage would say.

Once we begin to acknowledge that there is a problem, or when we are more open to the idea that something needs to change, we move into Contemplation. Here we know that something needs to change, but we’re not exactly sure if we’re ready to go through with it. Basically, when an individual is in the Contemplation stage of change, they’re “sitting on the fence”: A part of them wants to change, but another part does not. We will make excuses for not changing, but we also articulate the benefits of changing. It’s a hopeful sign that something is happening.

When we make the decision to change, we need to prepare for it, hence the Preparation stage. This is when we start to “test the waters” of change. For example, we may purchase a new pair of shoes for exercising, or we may look at our weekly calendar and schedule time for exercise.

When we make the decision to change, we need to prepare for it, hence the Preparation stage. This is when we start to “test the waters” of change. For example, we may purchase a new pair of shoes for exercising, or we may look at our weekly calendar and schedule time for exercise.

Once we actually start to engage in the new behaviour, we enter into the Action stage. This stage is defined by small behavioural successes. What is important to recognize here is that even though the individual is engaging in the new behaviour, they still have not made it a regular part of their lifestyle. In other words, more time needs to pass in order for change to be completely achieved. After regularly engaging in the new behaviour (usually after 3 – 6 months), then we enter into the Maintenance stage. This stage reflects the individual’s commitment to change and suggests that the personal rewards and gains achieved is in itself a motivation to continue.

Some versions of the Stage of Change model depict a Relapse stage. This stage is characteristic of a return to old behaviours, or the absence of the new one. It highlights the fact that despite our best intentions, there will be setbacks and ‘slips.’ However, every episode of relapse is a powerful teaching moment. Whenever we relapse into old patterns, we learn more about the barriers and obstacles that prevented us from remaining in the Maintenance stage, and now have more insight into learning how to prepare for this trigger the next time we confront it.

Hoping your week is filled with much knowledge and growth.

(Richard Amaral, Ph.D., is a registered psychologist in private practice. He works with children, youth, adults, and families)